After heavy bombing during WWII, Chemnitz was given a modernist makeover and rebranded Karl-Marx-Stadt.

A huge bronze head depicting Marx still stands in the centre today, however the city’s socialist urban plan has since been infiltrated by new commercial developments.

Saxon Manchester

Chemnitz lies at the foot of the Ore Mountains, around 80km from Dresden. The city was established in the 12th century, and was known as a notable trading place on the salt route to Prague.

By the 1300s, it had gained a central role in textile production (particularly linen and bleaching), which remained its prime industry for many years. At the forefront of industrialisation, it was home to Germany’s first spinning mill, which opened in 1800.

Throughout the 19th century, the settlement began to witness drastic growth, fueled further by the coal mines and lignite fields established in the surrounding areas. This and the bustling textile industry earned it the nickname ‘Saxon Manchester’.

Ich hab’s gewagt

By the turn of the century, Chemnitz was Germany’s wealthiest city. The population tripled to 300,000 by 1910, stimulating its development.

In 1855, teacher Johann Stahlknecht built the first house in Kaßberg, a hill leading down to the centre. He inscribed with “Ich hab’s gewagt“ (I dared to do it) because at the time the area was completely derelict.

Soon residential houses were built there, and the area became home to one of the highest concentrations of Art Nouveau architecture in Europe, housing some 480 works.

Between 1883 and 1915, the city authorities continued to ramp up the infrastructure and built a market hall, power station, town hall, hospital, and a gasworks. Offices were also built, as companies such as the Auto Union (now Audi) established their businesses there.

This era also saw the development of Theaterplatz, a pedestrian square which is lined by the neoclassical Chemnitz Opera House and King Albert museum.

A Cog in the Machine

Along with textiles, machine production also became one of the city’s main industries.

This made Chemnitz an important ‘cog’ in the Nazi war effort, with many factories producing military hardware, such as airplane parts and machine guns.

With its economic prosperity and central role on the production line, Chemnitz was a prime target for bombing during World War II.

By the time the war was over, some 80% of the inner city (within a six-kilometer radius), was completely destroyed.

The Birth of Karl-Marx-Stadt

Following the war, Chemnitz was incorporated into the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

In 1953, the city was rebranded Karl-Marx-Stadt, to coincide with ‘Karl Marx Year’, which commemorated the 70th anniversary of the philosopher’s death.

Initially, reconstruction was implemented according to the old city plan, with repairs carried out on the Roter Turm, a tower that dates back to the 12th century, and Theaterplatz, which had the misfortune of being briefly named ‘Adolf-Hitler-Platz’ during the war.

By the 1960s however, a second plan was introduced by East German architects that embraced socialist urban planning. The centre was redeveloped according to the principles of the modernist movement, with a strong emphasis on function over form.

The bombed-out 19th-century buildings, such as those on Kaßberg were neglected, while urban planning focused on the industrial redevelopment and the reconstruction of residential housing.

The Nischel on Skull Alley

As part of the new plans, in 1971, a 40-tonne statue of Marx’s head was unveiled in the city centre in front of 250,000 people.

Believed to be the second-largest bust in the world, it measures 42 metres high and was created by Lev Kerbel, a prolific Soviet sculptor.

The artist cast the skull in 95 pieces in Saint Petersburg, before shipping them over and welding them together.

It was placed in front of the SED headquarters (now the finance and tax office), and soon earned the nickname of ‘Nischel’, a Saxon nickname for skull, while the road it was placed on was referred to as ‘skull alley’.

Modernist Redevelopment

Opposite the statue stands the City Park, the Inter Hotel and Stadthalle, which were developed from 1969-1974.

With its colossal polygonal facade, layered by precast concrete elements, the Stadthalle is one of the city’s landmark buildings.

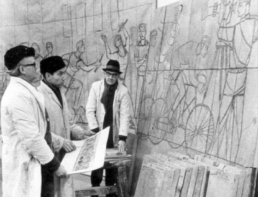

The entrance hall is just as striking, with a mural titled “The liberation of science through the socialist revolution”, by Horst Zickelbein stretching across the foyer.

The park outside the Stadthalle is also filled with art – mostly sculptures created according to state-mandated topics such as ‘Dignity, Beauty and Pride of Man in Socialism’ and ‘Productive Power’.

This development is intersected by two main streets – Karl-Marx-Allee, on which demonstrations and parades would take place, and the Street of Nations – a wide boulevard where there are cafes, offices, and a smattering of sculptures.

Belz’s Mark

Around 350 works of public art from the GDR era can be found in the city today. One of the most prolific contributors was Johannes Belz, a sculptor from Pomerania.

He began creating pieces, such as led-inlay murals on residential buildings, as early as the 1960s when the modernist plan was first implemented.

Pieces by him are dotted around the city and take many forms, from the flower-like sculpture made out of Soviet stars that stands outside the InterHotel, to the musical fountain at Chemnitz bus station. However his final piece, which remains unfinished, strikes poignantly.

In 1968, Belz was commissioned to create a bronze relief that would demonstrate the victory of socialism. The artist had allegedly struggled to draw up a draft of the piece, having found it difficult to provide a vision of the future of life under the governing party.

Shunning socialist realist styles and topics, he started to work on a more abstract vision, however this stance was not something that was welcomed by party officials.

In 1976, the artist took his own life in his atelier, where he had been working on the piece. The unfinished work, titled the ‘Fight and victory of the German working class’, still stands today on the corner of Bahnhofstrasse and Brückenstrasse.

Economic Decline

There is no doubt that Belz’s despair was indicative of a growing despondency among citizens in the GDR.

Although Karl-Marx-Stadt had continued to be an industrial centre, it could not be safeguarded from the economic problems that ensued in the 70s and 80s.

All decisions had to go through the ruling SED party, which asserted a structural rigidity that made it wholly inflexible.

The East German economy was also heavily dependent on the Soviet one, so when the latter started to collapse in the 80s, circumstances toughened for the GDR.

In October 1989, around 700 people took to the streets to protest for economic and democratic reform. One month later, the wall came down in Berlin, signaling the start of Germany’s reunification.

Name Change

In 1990, a petition called for the city to revert to its historical name, with some arguing that they were never consulted regarding the change to Karl-Max-Stadt.

In April that year a vote was held, and 76% of the population voted for the city to be rechristened Chemnitz.

With a new name, came a new city plan, and an architectural competition was announced in 1991, which attracted commercial firms to push their designs for the redevelopment of the city centre.

Among the new projects were Hans Kollhoff’s Galerie Roter Turm, a shopping mall with brick arches that pays tribute to the city’s historical landmark, and the glass and steel Galeria by Helmut Jahn. Overall, 66,000 sqm of commercial space was introduced.

The new shopping malls however weren’t enough to deter people from leaving, and by 1996, the population had dropped by 40,000, with many leaving to seek opportunities in former West Germany.

Today, the core pieces of Chemnitz’s socialist architecture are well-preserved, and the Nishel remains a central point of orientation for the city’s residents.

Many protests, gatherings, and fairs are regularly held in front of Marx, and although the city has changed its name, the bust won’t be budging any time soon.