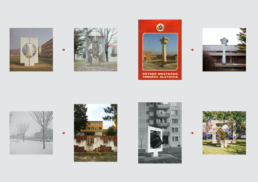

The Slovakian city of Trenčín was once home to over 100 works of public art, yet many have disappeared over the years.

Collective Hlava5 are on a mission to document the eradicated works and save the remaining ones, scrupulously mapping the diverse range of pieces through an online map.

We caught up with the group to learn more about the process, and what led to the project’s creation.

When did you start Hlava5?

The project started in the summer of 2017, after a successful solo exhibition dedicated to local architect Ján H. Blicha. His grand-daughter Lucia Mlynčeková had been researching his work, which was quite diverse in scale. He did big development projects creating urbanism plans for entire suburbs of the city, public building projects, family houses and also public artworks. The artworks caught her attention in particular, so she decided to explore this subject closer, leading to the creation of Hlava5.

Why do you think it’s important that such works be preserved?

In the process of researching and collecting all available data about public art in our city, we discovered that a lot of the pieces are lost forever. In some cases, the aspect of destroying the artwork was understandable, sometimes they were a powerful gesture towards transforming our society after the revolution.

In most cases a lot of ‘innocent’ artworks were lost because of a lack of public interest, and little money for their repairs and regular care. We are the first generation after the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, so we see things differently. For us they are not simply pieces of propaganda, manifesting force and fear. We see superior artworks by prominent artists, an influential part of our public space, that are part of our history and memories. We are very sorry when these artworks are connected or associated with negative feelings and memories, so we are trying to show the people their true value, their meaning and the beauty that is generally overlooked.

What is the government’s stance on their preservation?

We are very lucky to have had support from our local council and the department of architecture and urban planning in Trenčín. They supported the project from the very beginning and they are helpful in every activity we come up with. It is very important for us to be part of the community, so we also collaborate with local activities such as public art tours on bikes or with a small local urban festival called ‘Priestor’ (Space). Trenčín is a great place to manage bottom – up and top – down projects hand in hand.

Are there ever works that are found in ‘unexpected’ places?

At the beginning of the project we didn´t know the exact laws that were in place during the communist era. So at first it was a little chaotic and we had to explore the whole city, every single area, every single archive file. But after some research we managed to understand the logic behind the presence of the artworks. From 1965 until 1990 law no. 335 was implemented in Czechoslovakia. The law stipulated that a certain percentage of funds from the public building budget must be used for implementing public art. The percentage ranged from 0.5 to 4 % depending on the ‘social’ importance of the planned building. So the position of the artworks is understandable now – they had to be visible in the most frequently used places such as the front facades, portals, and foyers. From time to time the buildings change their function, or they are completely reconstructed so they look like they´re from a different time period, or the artworks are moved to a different position. These situations are somewhat ´unexpected´ for us.

Do you find that attitudes towards them change depending on their form?

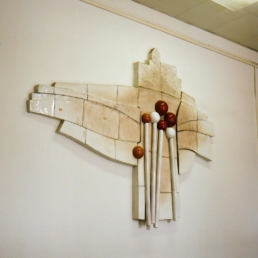

Of course, the form is very important for the people. The appearance is one of the subjects of art that is the easiest to relate to. On the other hand, some of these artworks don’t have to be necessarily beautiful to become a part of the public space, to become a symbol. Unfortunately, back in the 90s people didn’t care about the value or the meaning of the artworks during reconstructions or development, so it was very easy to remove a relief, sell a metal sculpture or to cover a mosaic with thermal insulation. The ‘luckiest’ are the big and heavy concrete sculptures. So facts like those are important, people are familiar with the forms, because sculptures are everywhere, they are not ‘new’ or ‘unknown’. From the stories of the people, one thing that was most important part was the aesthetic quality of the sculpture, and then also if it was possible to climb on it and play around it.

Do you find that the willingness to preserve them is dependent on how ideologically imbued they are with the country’s socialist past?

We are currently working with our local council on the process of preserving the artworks. We started with the work of Ján H. Blicha, whose work has never been politically leaned towards communism and never represented forms propaganda. Of course, there were artists or architects, whose art was quite ‘neutral’ or sometimes ‘pro-political’, but our goal is to see those problems from the other perspective. It is not so black and white. Alot of these artworks were deliberately hidden or destroyed after the revolution, but we are not currently struggling with the dilemma of being ideologically correct.

Are there any stand-out works that were recently lost/demolished?

Unfortunately, yes. The motivation behind the process of research and collection of all these artworks is to make sure that the selling or demolishing of a public artwork won’t be possible in the future. Recently many schools, malls and hotels were reconstructed, so a lot of reliefs and mosaics were covered with insulation in order to abide by state regulations.

Was there ever a kind of ‘decommunisation’ process in Slovakia concerning public art?

There was plenty of art purposely destroyed after the Velvet Revolution, mainly to show that there is no space for the propaganda, no space for the presence of their symbols, no space for the presence of sculptures of the ‘powerfu’ politicians watching over us. The process of hiding and destroying symbols was meant as a gesture of freedom. I am not sure if there was ever an organised act of ‘decommunisation’ in Slovakia, but a lot of artworks ended up disassembled and archived in museums and galleries.

Perhaps one of the most iconic acts of destruction was in November ´89 when the sculpture of Czechoslovakia’s first president Klement Gottwald was taken down in Bratislava.

The statue was too big to be disassembled or taken somewhere else, so it was destroyed with explosives by professional pyrotechnicians in November 1990.

During our research in our hometown Trenčín, we found only a few examples of these typical monuments of propaganda. There was a propagandistic mosaic present in the local municipal office, but as we discovered, the artwork is still on its original place but only covered with plaster board wall. The other example was a famous symbol of communism – the hammer and sickle. We have no idea what happened to the original sculpture, but we discovered a smaller prototype scale model in the deposit of a local museum.

Would you say there is a large number of public art works in Trenčín compared to other similar-sized towns? If so, why do you think this is?

There were more than 120 pieces of artworks within Trenčín’s 82 km radius, so I personally think it is an admirable amount. The number of these artworks was dependent on the growth of the city during the communist era, as all the developments were created hand-in-hand with these artworks. In the 60’s, when Trenčín had around 39,000 citizens, there was an ambition to make this number grow to 100,000, but it stopped at around 58,000.

It was also dependent on the cultural scene in Czechoslovakia. There were several events that were very important for the presence of art by great sculptors throughout the country. For example, Vyšné Ružbachy (SK), Piešťany (SK) and also Ostrava (CZ) had international symposiums that resulted in large collections of sculptures in parks of the cities.

What kind of backgrounds do the members of the group have? Are you architects/graphic designers?

The team is slowly growing. Currently there are eight people who have different roles in the project. All the graphic work is mainly made by our team leader Lucia Mlynčeková with help from Michaela Mrázková that also designs our merch. Prokop Harazim is a product designer, Alexander Topilin is an architect. Adriana Mlynčeková is an architect and urbanist working on the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning of Trenčín. Terina Barčáková is an event manager, also responsible for the urban festival Priestor in Trenčín. Matúš Kaščák is our photographer and Michal Hornák takes care of our website.

What do you have in mind for the future? Do you have any plans for any other additions to the project?

We are currently working on cleaning a few of the artworks and also preparing for the complex reconstruction of one sculpture with financial help from the city. If this collaboration continues, we would like to take care of the artworks that need repairs. Our plan is to publish our collection of the artworks in a book. We are planning to make a blog on our website where you can see our progress and activities. We’d also like to organize an event with guests from different groups that are also focusing on public art and cultural heritage from communist era in Czechoslovakia so we can meet and discuss all the different approaches and ideas we have. And finally, we would like to present our project abroad so we are working at some open call offers and exhibition proposals to get the opportunity to exhibit our work in Europe.